It's Admissions Season!

Come visit our campuses or learn more about WSP’s transformative preschool-12th education.

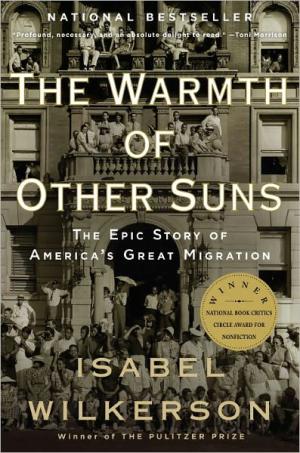

The daughter of parents who fled the South and Jim Crow, Isabel Wilkerson sought real stories from real people. She was the first black woman to be a Pulitzer Prize winner, and the first African American to win for individual reporting, at that. Wilkerson dedicated fifteen years to the making of this six-hundred-page book, interviewing over 1200 individuals documenting the widespread phenomenon that was the Great Migration.

The daughter of parents who fled the South and Jim Crow, Isabel Wilkerson sought real stories from real people. She was the first black woman to be a Pulitzer Prize winner, and the first African American to win for individual reporting, at that. Wilkerson dedicated fifteen years to the making of this six-hundred-page book, interviewing over 1200 individuals documenting the widespread phenomenon that was the Great Migration.

“Such may be the sheer force of determination of any emigrant leaving one repressive place for something he or she hopes will be better. But for many of the migrants from the South, the stakes were especially high – there was no place left to go, no other refuge or other suns to search for, in their own country if they failed. Things had to work out, whatever it took, and that determination showed up in the statistics.” (Wilkerson 530.)

These stories that Isabel Wilkerson brings to paper capture the desperation of the times. There was a blind faith that so many people simply had to put in their plans of leaving the south because they had no other choice. The times were cold, and there was word of sunshine in the north.

Isabel Wilkerson translates real life experiences gracefully on the page, blending these three stories with information and context of the times with care. She shows us experiences from people who would have otherwise blended into history as simply a small part of the great phenomenon that swept America. She brings these similar yet very different experiences to light for us, following three of millions who had gone in search of warmth.

I recommend reading this book because the switching of focus on different main characters saves from a droning on and on about one person. You’re allowed to take a break from someone’s story and read something new without having to put down the book. It adds depth to the whole of the reading and learning experience, as sometimes the material can get to be a lot. This book gives the reader a view through the eyes of three people who had to find their ways in the dark, trusting that they would reach a light to bring the warmth of other suns.

Read more student perspectives in the Waldorf Chronicles, a newsletter run by WSP high school students.

I recently got a job working at a restaurant and after a couple of weeks the abstract concept of food waste became concrete in my mind. It was no longer just the idea of food being lost, I was starting to see real food wasted. And much of the food being thrown out was still perfectly edible! It could probably be reasonably inferred from the contents of any restaurant’s dumpsters that humans have an excess of available food. But we see in the world as well as in the United States that that is not actually true.

Imagine you have a pound of food in front of you. For a visual, that’s about the weight of a bowl of pasta. That is how much food is wasted every single day per person. This means that every day, for every person in the world, a whole bowl of pasta is lost. That is equivalent to over seven billion bowls of pasta wasted every day. One pound of food per person per day.

In the United States, a whole thirty to forty percent of available food goes to waste, and the reasons it goes to waste vary a lot, ranging from farming practices to cooking practices. During every step food takes to reach our mouths, food is wasted.

The first concern comes with the fact that we are, in fact, wasting thirty to forty percent of our food, and in turn, putting too much effort and labor into something that will never see the light of day (or the inside of a stomach). We are losing so much money paying for workers whose work ends up being wasted. This, and the food insecurity we see all around us today, are reasons food waste is an important topic.

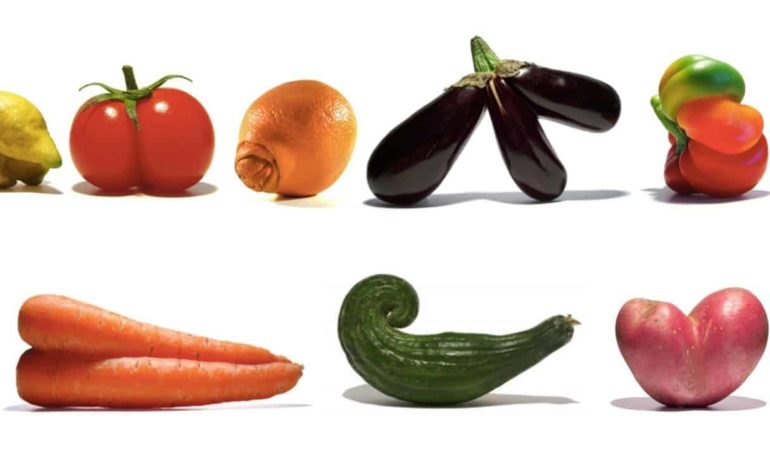

One reason that waste is so commonplace is how we unnecessarily nitpick what food reaches stores. Companies will reject food that doesn’t look the way a customer might imagine, because it’s been shown that people are more likely to buy visually aesthetic food than “misshapen” food. This problem is in the process of being overcome, with companies like Imperfect Foods selling “misshapen” produce (like that in the picture above) so that it doesn’t go to waste.

A large contributing factor to food waste is over purchasing. This is a problem both in average households and, to a much more dramatic degree, in restaurants. What we as average citizens can do is to keep over purchasing to a minimum. Buying too much food ultimately leads to that food being thrown out for spoiling or for lack of need. If we all limit what we buy to what we need, food waste would be reduced on a small scale. The restaurant industry, on the other hand, has a larger impact on the creation of food waste. Restaurants need to buy extra food, as is understandable, because of the nature of the industry, but there must be better ways of dealing with leftovers than to simply throw them away at the end of the day. Restaurants could, at the end of the day, take the edible food that was destined for the trash and instead offer food to people in need.

This is not a completely hopeless fight. We may have no control over the restaurant industry or the packing and processing of food, but we do have control over what we buy and what we throw away. The things we can do to reduce the amount of food waste is to buy the amount of food we need and to only throw out food that is inedible. There’s no reason so much food should be going to waste, especially considering the large number of households that are food insecure.

Sources:

Cooper, Ryan, Food Waste in America: Facts and Statistics, Rubicon.

Food Loss and Waste, FDA

USDA’s Food Waste FAQs

Feeding America’s How We Fight Food Waste in the US

Read more student perspectives in the Waldorf Chronicles, a newsletter run by WSP high school students.

Experiential Interdisciplinary Week (better known as EI Week) is a week-long engaged learning process in which high school students at WSP “learn by doing”. The planning of EI Week starts in winter when high school faculty and students submit proposals for workshops based on the theme that WSP adopts to explore as a whole school community. This academic year, the school established “togetherness” as the appropriate theme when our school community transitioned back to campus for in-person learning. EI Week learning activities can include, but are not limited to, a hands-on learning approach, day and overnight trips, field explorations, guest speakers, community service, art, music, performances, and so forth.

The workshop in which I participated was titled “Exploring Bay Area Diversity ” and the main intention was to bring more awareness that would give students a platform to discuss the quality of equity and actual representation of Bay Area communities by looking through the intersectional lens on social issues.

A group of eleven students and two faculty advisors had several planning sessions and discussions to form what we envisioned the week would be like for us to bring the proposal into a reality. In these meetings, our group members began to brainstorm, discuss and disagree, collaborate and combine ideas, lead and follow each other until we arrived at the basic framework of what our group would be doing together for a week. Basically, the piece that stood out for most of us was the challenge to visualize or verbalize intersectionality.

Eventually, we shifted our focus to include all types of diversity while promoting and celebrating inclusive environments that strive to make everyone living in the Bay Area feel like we belong here. Our group was clear that we wanted to incorporate community service, explore historical aspects of migration into the Bay Area, deepen our understanding of racial equity and systemic issues, eat good food, celebrate art, music and culture of various communities, and spend time capturing our experiences through photography, journaling, poetry, story-telling, painting, drawing, learning, creating, and questioning.

The biggest take away from this experience is that our group learned that there are pockets of segregation across different counties. There are also the invisible communities who have very little access to healthy food, proper shelter, education, health care, childcare, employment issues, and equal wages, as well as immigrant rights. Our exploration clearly brings out how segregated the entire Bay Area is. That segregation impacts economic outcomes: a racial segregation that leads to economic segregation. The housing crisis in the Bay Area impacts all of us in its own way as well. The most humbling moment of this entire experience was when we met with Erika Huggins for an entire afternoon while she led our group through the streets of West Oakland and shared her biography and history of the Black Panther Party. With deep wisdom and courage, she conveyed that we should try to talk about these things in a broad framework of humanity. How do we treat our fellow human beings?

Othering certainly is a mechanism by which we are trying to segregate people: ‘us’ versus ‘them.’ So, it’s important that our generation look at this moment through the lens of ‘othering and belonging,’ and see that if we have a more integrated community, we are actually lifting up everybody. We are lifting up the entire society. We are all living together.

Other EI Week workshops looked at Food Systems, went on various Outdoor Adventures, and explored sustainable fashion.

Dylan Lee is a regular contributor to the Waldorf Chronicles, a newsletter run by WSP high school students.